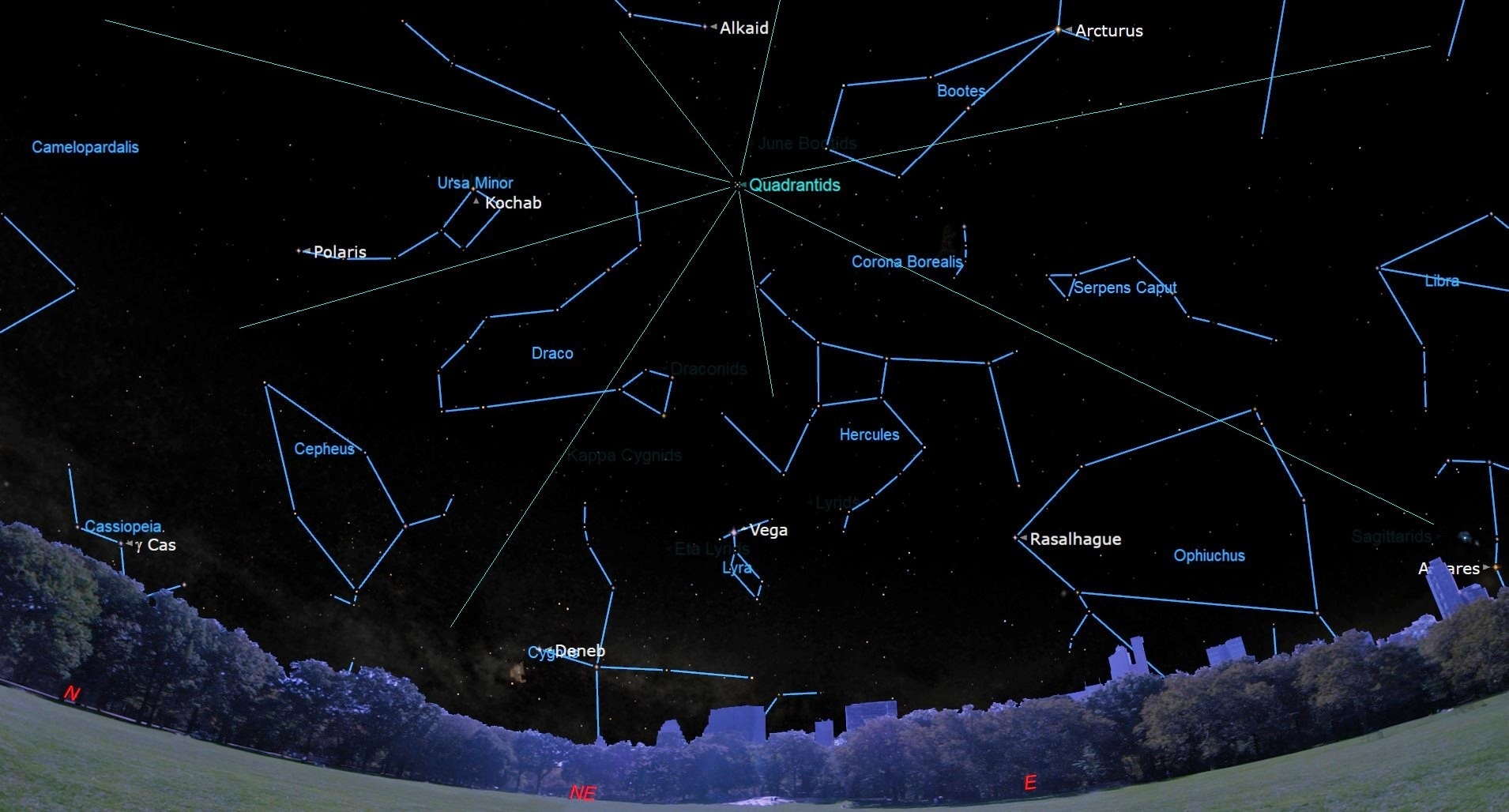

Early each January, the Quadrantid meteor stream provides one of the most intense annual meteor displays, with a brief, sharp maximum lasting only a few hours. For this reason, many stargazing guides make reference to this display as being particularly elusive. However, in 2025, viewing circumstances favor North Americans, particularly those living west of the Mississippi.

The meteors actually radiate from the northeast corner of the constellation of Boötes, the Herdsman, so we might expect them to be called the “Boötids.” But back in the late 18th century there was a different constellation there called Quadrans Muralis, the “Mural or Wall Quadrant” (an astronomical instrument). It is a long-obsolete star pattern, invented in 1795 by J.J. Lalande to commemorate the instrument used to observe the stars in his catalogue. Adolphe Quetelet of Brussels Observatory discovered the shower in the 1830s, and shortly afterward it was noted by several astronomers in Europe and America.

Thus, they were christened “Quadrantids” and even though the constellation from which these meteors appear to radiate no longer exists, the shower’s original moniker continues to this day.

Remnants of a long-dead comet

At greatest activity, 60 to 120 meteors per hour should be seen during the 2025 Quadrantid meteor shower.

However, the Quadrantid influx is sharply peaked: six hours before and after maximum, these blue meteors appear at only half of their highest rates. This means that the stream of particles is a narrow one — possibly derived relatively recently from a small comet.

In fact, in 2003, astronomer Peter Jenniskens of NASA, found a near-Earth asteroid (2003 EH1) that seemed like it was on the right orbit to make the Quadrantids. Some astronomers think that this asteroid is really a piece of an old, “extinct” comet; perhaps a comet that was recorded by Chinese, Korean and Japanese observers during the years 1490-91. Maybe that comet broke apart, and some of the pieces became the meteoroids that make up the Quadrantid stream.

When and where to look

In 2025 a moderately strong display of Quadrantid meteors is likely for North America, particularly over the western half of the continent. According to Margaret Campbell-Brown and Peter Brown in the 2025 edition of the Observer’s Handbook of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, maximum activity is expected at around 10 a.m. Eastern Time or 7 a.m. Pacific Time (1500 GMT). Just before the break of dawn, the radiant of this shower — from where the meteors appear to emanate — will be ascending the dark northeastern sky.

This is also the time that the dawn side of the Earth is facing forward in our 18.5-mile (30 km) per second face around the sun. This added velocity also means that our upper atmosphere strikes more meteors, and hits them harder, thus making them appear brighter, as opposed to when meteors come at us from behind during the evening.

Those who live in the eastern half of North America will be seeing the “Quads” increasing in intensity before bright morning twilight and sunrise intervenes, with a single observer likely to see rates of 20 to 40 per hour. For those who live in the western half of North America, meteor rates will probably be even higher, possibly even approaching their absolute peak rates of 60 to 120 per hour.

With no moonlight to interfere, this might turn out to be one of the best meteor displays of the year.

But be sure to bundle up!

Lastly — and we’ve touched on this point before, but certainly it should be addressed again: Likely your local weather will be more appropriate for taking in a hot bath as opposed to a meteor shower. And indeed, at this time of year, meteor watching can be a long, cold business. You wait and you wait for meteors to appear. When they don’t appear right away, and if you’re cold and uncomfortable, you’re not going to be looking for meteors for very long!

Therefore, make sure you’re warm and comfortable. Warm cocoa or coffee can take the edge off the chill, as well as provide a slight stimulus. It’s even better if you can observe with friends. That way, you can cover more of the sky.

So bundle up, good luck and enjoy this meteor show(er)!

If you want to try your hand at photographing the Quadrantids or any other meteor shower, check out our guide on how to photograph meteors and meteor showers. And if you need new imaging gear, consider our best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York’s Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers’ Almanac and other publications.

Article by:Source